History of Washington services

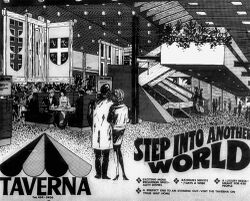

The restaurant area in the 1970s.

Washington attempted to be something special: it was Taverna's first site and they were keen to be revolutionary, with their love for walkways and automation, but it had a steady decline into becoming very indistinct.

Site and Operator

See also: A1(M) Service Area Planning

Esso already owned a petrol station here, known as Port (as in Portobello), which they had already drawn up plans to expand by adding a restaurant and hotel. A small restaurant was already provided on the northbound side.

When the A1 was upgraded to motorway, Esso asked if they could save the Ministry of Transport the £200,000 they were due in compensation (around £3million in 2025) in return for permission to build a motorway service area here.

The Ministry were starting to struggle to find anybody who was keen to build a service area, so they agreed to bend the rules for Esso. Another possible site at Pea Flatts, which would have been an infill site, was considered but Washington was the better option.

Owing to the unusual agreement arranged with Esso, they were told they wouldn't need to be open 24 hours, and the new service area would be built by the motorway contractor to allow for a phased construction. It was the first site to be allowed to sell only brand of fuel, which naturally was Esso. It was all stacking up to be a sweet deal and a desirable site for Esso to launch their new venture.

The old petrol station closed on 1 June 1968, and the direct access from Portobello View was closed. The new buildings had to fit around the existing terraces, but the Methodist Church was demolished. Several houses on Portobello Road now had a front-facing view over the parking area.

Naming Contention

Much of the time planning the service area was spent naming it. Esso asked if their original name could be changed because at the time motorway services held a much higher profile than ordinary petrol stations, and they felt the phrase "Esso's Port Services" would be confused with other projects they were working on.

When designing the motorway, the Ministry used a temporary name of Vigo for this service area, but later confirmed that it would be called Washington. Chester-le-Street Rural District Council objected to this, and wanted it to be called Birtley. The Ministry's decision was probably inspired by the excitement around Washington being designated a new town in 1964, while Chester-le-Street were conscious that it was being built on their land and Washington wasn't in their remit.

After much debate, the Ministry reluctantly agreed to settle the matter by officially renaming it Washington-Birtley. When Esso heard this name they were not impressed, as they felt the new name was cumbersome and difficult to market. They suggested customers would ignore the "Birtley" part.

The service area did open as Washington-Birtley, but with much marketing material referring to it as just Washington. After some time Granada officially shortened the name. Highway authorities sometimes still refer to the site by its full name.

Meanwhile, Esso decided to operate their facilities under the brand name 'Taverna'. It was the launch site for the new brand, with a blueprint that was going to be copied across several more upcoming projects.

Design

The new building occupied a 12 acre site.

Esso initially wanted the main amenity building to be on the west side. Amongst other considered options, Esso looked at having the second storey of the southbound building hang over the access road. The Bartlett Report of 1967 found that service areas heading away from urban areas are much busier, so putting most of the facilities on the southbound side was a wise move.

The Ministry also looked at tying the northbound service area into the junction south of here, to try to overcome the difficulty of how to efficiently lay out the parking areas in such a tight space. The County Surveyor had wanted the service area to have a subway instead of a bridge to reduce its visual impact; instead both a striking bridge for the public and a private service tunnel were provided.

Opening

Esso, 1972.

The design of the building was inspired by the idea of air travel. Its advertising tried to appeal to well-travelled people who often visited mainland Europe.

As part of its desire to be futuristic, the food it offered was part-cooked, then put into a vending machine where customers could buy it and carry it to a microwave along with cooking instructions. This was quite novel at the time, and the Ministry had severe concerns that motorists would not take well to the automated catering.

Esso boasted that you could "cook your own meal in 40 seconds". Adverts were issued with the slogan "step into another world" and "a perfect end to an evening out". It was called a "gateway to Tyneside", but it was aimed mainly at people who lived locally, whom Esso claimed to have "captured the imagination" of.

The futuristic catering was really about getting motorists in and out the building as quickly as possible, as the car park was only small. Their consultants had recommended automation to ensure a high turnover. There were 420 fixed seats in the main restaurant, 80 in the transport café, and parking for 285 cars, 70 lorries and 12 coaches.

When it opened, the footbridge, which spans five carriageways, was the longest in the UK. The roof was lined with reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete. The northbound side had an escalator taking people up into the "futuristic and robotic" southbound facilities. This escalator was later replaced by a more soulless staircase.

In the main amenity building, visitors from the northbound side arrived on a raised walkway, offering a view over the serving area. This walkway still survives, but the excitement has been lost. The land slopes towards the south, allowing for a below-ground floor that overlooks the HGV parking area - this was used as a transport café. This was also useful for hiding a deliveries bay, and ensured the amenity building wasn't too obtrusive in this suburban environment.

The steep slope and cramped site meant that a concrete retaining wall that runs along the edge of the car park and HGV parking area became a key feature of the outdoor environment. A winding, concrete pedestrian walkway provided rear access to the building from the HGV and coach parking. This was originally supposed to be temporary but was later accepted as being permanent. Around here was a small amount of shrubbery, which is still there, but difficult to access. A third entrance is provided for HGV drivers next to the delivery bay, with a very discrete doorway.

The northbound building also had two entrances. The rear entrance, which linked to the HGV parking area, crossed the slip road with a pedestrian crossing very close to the motorway exit. This access was diverted when the second hotel was built on the grass space, and the doorway became part of what's now the Costa area.

Failure

Department of Transport MSA Branch, 1973.

The failure of the automated catering trial at Washington was very-much the cause of the failure of Taverna.

Taverna had struggled to buy in the part-cooked food that their vending machines needed. They also found that the machines were unreliable, and needed to be loaded with change frequently. Customers weren't navigating between the vending machines in any order, causing the crowds to cross over. However the biggest problem was that most people simply weren't willing to give the vending machines a go.

Washington tried to solider on with a mishmash of half-automated half-waitress service catering. It was described as "grossly underused", "a very poor service" and the experiment was summarised by the government as "a howling flop".

When Taverna were looking for a buyer in 1973, eventual owners Granada would have done anything to avoid getting Washington as part the deal. Taverna were so desperate to lose it that there were real fears it could be abandoned. Granada wanted Taverna's other sites, and eventually accepted that they'd have to get Washington with them.

A 1977 assessment of service areas concluded Washington was one of the quietest in England, because it is "simply in the wrong place". The theory about building close to a city had been totally wrong.

After Taverna

Under Granada, the service area moved to their usual low-cost model, which tried to make the most out of the trade available. The northbound facilities were expanded to cater for people who weren't prepared to cross the bridge, however trade remained disappointing. The new northbound shop only opened on weekends and the new northbound restaurant only opened in high summer; at all other times, people still needed to climb the steps.

Although by now most people had shortened the name to just 'Washington', the road signs still said it was officially called 'Washington-Birtley', until at least the late 1970s.

The restaurants were refurbished in 1989, with a Country Kitchen Restaurant introduced to both sides. Egon Ronay called them "pleasant enough", but graded the overall experience as "poor". These would later become a Little Chef on the northbound side, and Fresh Express on the southbound side, extending the northbound opening hours.

The truckers' café was closed in the late 1990s, and in the late 2000s the free-flow restaurant was reduced to offering a Burger King and Costa only - one of the first to head this way.

In 1995 the Highways Agency sold the freehold for this service area, but Granada were outbid and instead a private investor picked it up. It's not clear whether this has since been rectified.

The Highways Agency carried out a road safety scheme in late 2008. This involved providing mesh fencing between the service area and the motorway, and re-marking the harrowing southbound exit to make it look slightly more conventional.

Despite the café closure, Washington was still included in the Highways Agency's 2010 truckstop guide.

The southbound Greggs store here was the first Greggs store in the UK to reopen following their decision to close all their stores in March 2020 due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. It reopened on 4 June 2020, when Moto also added a new Greggs kiosk to the northbound side.